Image may be found at TraceyEminStudio.com

Tracey Emin is certainly known in America, but she’s a household name in Britain. While many find plenty to praise or blame with regard to her work, she has nonetheless gained the ultimate showbiz imprimatur—a relentless cadre of paparazzi. According to Dallas’ Kenny Goss, “Even cabbies know who she is; everyone there knows who she is. It’s the same with George (Michael). They follow their lives and they stay with them because they’re literally part of British history.” He should know. Goss and his former partner, pop star George Michael, met Emin at the spendy London restaurant, Ivy, after Michael had seen her on a BBC documentary and was smitten. The couple went on a hugely imaginative—not to mention preposterously extravagant—buying spree and acquired a vast collection of her work. Even now, when the subject of Emin comes up, Goss becomes infectiously enthusiastic. And it’s easy to see why. Emin has redefined what art can be and what a working-class background can mean. And, stunningly, she creates work that readily connects to confessional literature that spans centuries by giving it an utterly new, not to mention startling, visual dimension.

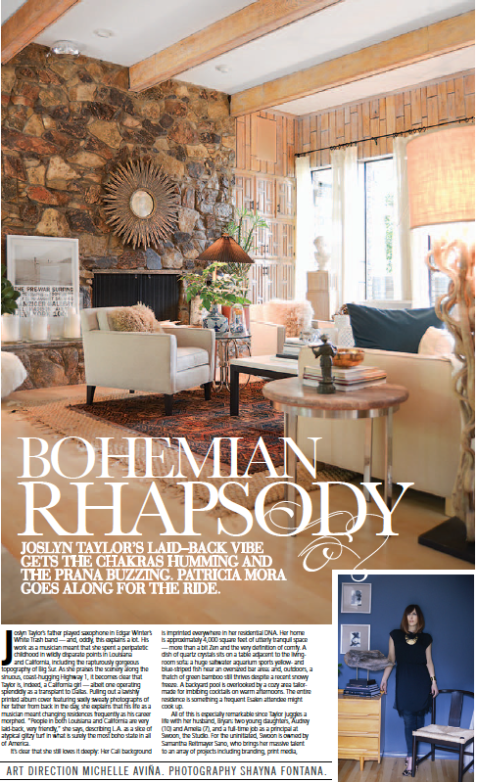

While Emin spends a great deal of time in London, she also periodically takes a working holiday near St. Tropez where she has an idyllic retreat just half an hour from the Mediterranean hot spot. Tucked away in the hills, it sits high above the coastline and is as close to a vertical axis as you’ll find on the Côte d’Azur; ironically, Emin, the oft-declared “enfant terrible” provides an ascendant vector for an otherwise playboy-infused, horizontal plane on the beaches of the Riviera. By some accounts her French home/studio is surrounded by such sinuous roads and convoluted trails that even she has difficulty finding it on dark evenings. A mere 25-minute drive from Jerry Hall’s neighboring residence can take Emin almost three hours by the time a circuitous route is thoroughly driven, recalibrated and re-driven—again and then again. One thing is certain: calling Texas from her remote location requires a satellite phone as well as conspiring planetary movements ruled the gods in charge of poetry, messages and communiqués.

While waiting on her call from the south of France, I did a bit of research on what it might be like to talk with Emin and ran across a chat between her and actress Joan Collins of “Dynasty” fame. So much for research. I was certain Collins and I have approximately zero in common since I’m short on both bling and a bevy of ex-husbands. However, Emin and I eventually connected and it was surprising to hear a voice on the end of the line that was pleasingly, even shockingly, soft. She said, “Hello, this is Tracey. Is this a good time to talk?” I assured her it was a perfect time to talk and asked if she had received my questions. (I, of course, had prepared questions for the superstar of the art world.) The answer was “No, I gave strict instructions not to be bothered.” Oh. That was a game changer—but no problem. I went on to introduce a bit of Q and A to someone who is basking in limelight as a newly minted Commander of the Order of the British Empire and enjoying a huge uptick due to the sale of her work—My Bed, originally exhibited in 1999—to a German Count. However, the aforementioned satellite phone was breaking up on my end while she confidently declared, “No, it isn’t. You’re perfectly clear and you’re speaking over me.”

Well, you get the idea. The woman is the most well known female artist on the planet, enormously wealthy, and has the folks you read about in Vogue on speed dial. Her work is collected by the likes of Orlando Bloom, Elton John, Naomi Campbell, and the aforementioned Jerry Hall. Not to mention: Dallas’ own Goss-Michael Foundation. Stunningly, however, a sleepy Tracey Emin was on the other end of my phone connection—after all, it was almost eleven in the evening in France—but there was not one rock star, super model or (even) champagne bucket in sight. Just the two of us. You know: engaging in a bit of art talk—which I admit I found mildly disconcerting, given her reputation for wild-child behavior.

I mentioned a quote from her regarding the role of art. Emin had noted that art was part of preserving culture. More specifically, she stated, “Art is the soul of our nation… If the soul isn’t looked after then everything will go to pieces.” She immediately remembered the verbiage and went on the describe art as the “custodian of the soul. Art protects the soul and, if the soul is damaged, art is there to recognize that fact.” She added, “There’s never been a moment when I was not creative, and art was there like a safety net.” The last bit was uttered with heartfelt insistence. And who could disagree? This is sounding quite buttoned-down and straightforward rather than a quote that could be chalked up as the ramblings of the art world’s outré renegade. Emin is now past fifty and was recently made Royal Academician by the Royal Academy of Arts. Her days of boozing and televised, blush-inducing invectives may be on the wane. Plus, her blunt desire to preserve and protect both our collective and individual psyches is both laudable and completely irresistible.

Gavin Delahunty, the Hoffman Family Senior Curator of Contemporary Art at the Dallas Museum of Art, states that her work, “Everyone I Have Ever Slept With, was an absolute sea change moment in the art world, along with My Bed.” He also notes that her work displays a vivid brand of “exploration and poetics, a confused anxiety—but she has emerged as a powerful and influential artist. It is now clear to everyone that her work has had a huge impact on art-making throughout the world.” Thus, Emin’s interior angst has been transmuted into trenchant art, lavish price tags, and worldwide adulation. However, even the sunny environs in France don’t alter her art or her fascination with the searing and weighty truths that thread their way in and through the human heart. Apparently, there are things even the Riviera can’t change.

Emin notes: “The art is the same, but it’s just easier to stay focused here because there aren’t the distractions that are in London.” Her demand that her studio manager not interrupt her work with my list of questions was eliciting concern on my part, and I quickly switched gears and mentioned my fondness for Goss. Any shred of Gallic brittleness was immediately banished, and Emin declared that the Goss-Michael Foundation “has so many pieces. They have a Tracey Emin museum!” She reiterated, “They have a huge number of pieces and a painting called ‘Hurricane.’” This was intoned in a way that emphasized the last work and her intense fondness for it. Goss says, “Every person who has seen that painting loves it!” It’s completely apparent that he is one of its foremost devotees. In the work, which is reminiscent of her line drawings on paper, a figure, frenetically depicted, seems to be emerging from an—equally frenetic—acrylic storm.

Emin and I covered some additional ground before she announced that she needed to go to bed, and we parted company. And, frankly, the phone call was mere icing on the cake for what is an already plum of an assignment. I feel as if I know her through her work far more deeply than could ever be conveyed via a phone conversation. In fact, I can’t help but put her in context with a long line of other confessional work that has held readers rapt for centuries. Most scholars agree that the genre was born in North Africa—ironically, a mere short flight over Mediterranean waters and less than 500 miles from the shores of France. I refer to St. Augustine of Hippo, who penned his Confessions, circa 397 AD, in such a way that it still reverberates with contemporary artists and memoirists. His work delivers a starkly frank account of his abundantly active sex life and his later move toward a—quite improbable—role as spiritual luminary for the West. Augustine’s work is a haunting and plangent cry for an explanation of why we do what we do. Moreover, he conferred upon us an ineluctable pull toward internal transformation. This was both completely new and a hook that worked then and still works now. Not because it’s contrived, but because it’s so deeply penetrating. He might well have deployed one of Emin’s mantra-like intonations: “Love is What you Want.” At this point it should be utterly obvious that some things are, indeed, timeless.

Similarly, Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote his own Confessions in the 18th-century in which he discussed masturbation. His candor sent the philosopher Edmund Burke into paroxysms of disgust with regard to the airing of “vulgar vices.” Burke’s remarks are in concert with what we still hear today with regard to Emin’s works, some of which also explore autoeroticism, as well as literary pieces that include Katheryn Harrison’s The Kiss and Toni Bentley’s Surrender—both of which address subject matter generally considered taboo. Memoirists’ works are endless and the personal purge shows no signs of abating. For that matter, did Jung ever write anything more thrillingly scintillating than his own Red Book? We relentlessly peer into it, hoping to glimpse vivifying insight into our own lives. We see other people’s wounds and psychic bandages as peep shows that confer wisdom regarding our own reasons for failing and flailing. We never seem to manage to perennially float on top of the world—and that troubles us. Thus, for the weary and searching, Emin delivers the goods. Rape, botched relationships, miscarriages, drugs, and booze. Her first solo show in America was held in 1999 at Lehmann Maupin Gallery. The title? “Every Part of Me’s Bleeding.” She produces unleashed, raw, anguished and, by turns, remarkably gentle work. She also tells us who we are by telling us who she is. We get the experience without the damage and the scars. Who can resist?

It becomes clear that wounds, Emin’s and ours, become apertures. They’re the means by which we learn to “see better,” a phrase from Shakespeare’s King Lear. And, it’s fitting that the same play describes a character as “seeing feelingly.” Perhaps no other phrase limns the manner in which art should be both made and seen. A significant power emerges from art that remains tethered to the body, when “seeing feelingly” remains the operative action. Interestingly, the literary market has been flooded with a slew of tales issuing from female authors who make no bones about their bodies—and what has been done with them and to them. In fact, the memoir genre flared with a fascinating rise in popularity in the 1990s and the attendant lurid details involving rape, incest, and substance abuse that were once deemed unmentionable suddenly were lauded for their candor and thunderous acts of disclosure. Even more fascinating—and surprising—is the fact that the aforementioned literary trend can be explored with nuanced deftness through Emin’s work.

She delivers the history of her life with complete authenticity, and this is done, in part, by reminding us that things are perpetually freighted with psychological import. Everything tells a story. Everything we touch or long to touch resonates with meaning. Thus, one of her blankets or installations is far more than a cluster of materials—it points us to a larger, richer arc than could ever be described by the calculus of everyday fabric and soiled or sewn items. There’s something far more mysterious at work. It’s a realm that isn’t seen but felt. And it is one Emin explores with a candor that is unmatched.

With the sale of her work, My Bed, to a German industrialist, Count Christian Duerckheim—who paid £2.54m for the piece and subsequently agreed to loan it to the Tate for at least 10 years—Emin has been an especially hot topic of late. And, as has been noted innumerable times, My Bed is freighted with used condoms, stained undergarments and bed sheets, booze bottles and cigarette butts. It’s an artifact that she dubbed art. And, arrestingly, this turned out to be a singular move that forever changed the manner in which confessional work and visual art can be understood. For one thing, it stridently underscores the fact that things are hosts for memory and other realms to which Emin frequently alludes in her own memoir, Strangeland. The book is one that British broadcaster, Jeanette Winterson, read and deemed so “painfully honest…(that) certainly some of it should have been edited out by someone who loves her.” The text is both emotionally eviscerating and haunting. In it Emin notes that her own appearance in the world bears the stamp of the accidental because her twin, Paul, pulled her into it. She claims that, otherwise, she simply would not be here—and certainly not present for the ongoing international conversation regarding contemporary art.

Given this slippery quality of the real—this meshing of realms—it’s important to realize that Emin gives us missives directly from the psyche. They’re unfiltered and undisturbed. And perhaps that is why we find them so unsettling. She confers upon us a reality that is ungoverned by empirical, Cartesian parsing—which, as an aside, remains the (antiquated) “skill set” many people still deem appropriate for looking at art. Emin holds fast to experience-as-image and therein abides a fullness that is lost when ruptured by limited or preconceived perspectives. She demands that we keep things whole and intact; in other words, Emin calls us to witness and share her pain, mystery, and shimmer. Whether we make the experience a temporary campfire or a lasting hearth is up to us. However, she ardently insists that we acquiesce to the experience of her (quite real) metaphorical heat.

Rainer Maria Rilke, the poet famous for his contribution to German literature, wrote:

“Things aren’t all so tangible and sayable as people would usually have us believe; most experiences are unsayable, they happen in a space that no word has ever entered, and more unsayable than all other things are works of art, those mysterious existences, whose life endures beside our own small, transitory life….”

Thus, Emin is easily inserted into company that is quite august. However, she would underscore the point that “art is real (and) it’s the other things that aren’t real.” And she does say things. Her neon sculptures are expert and starkly honest epigrams that speak volumes about matters of the heart as well as moments deemed sacrosanct. In fact, I asked Emin if things should sometimes be kept secret. After all, she is the epitome of a completely open, balls-to-the-wall truth teller. She answered, “Sure, some things should be kept secret, sacred things.” “Like what?” I asked. “Like love,” she responded. It’s been said that it’s the soft things that will break your bones. Emin delivers the whole panoply of emotions in ways that make us ache. And therein lies her capacity to stun us with her—quite remarkable—genius.

You must be logged in to post a comment.